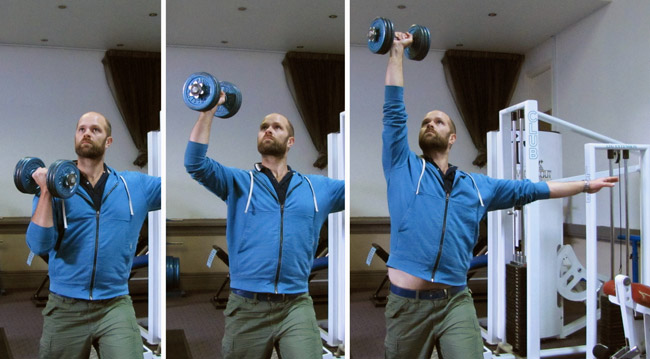

Strength training does not have to be complicated. All movements you can do at the gym, or kinda in ‘real life’, can be broken down into three categories: pull, push and squat. All exercises are some variations of these... depending on your point of view. You can break it down further – there are twisting actions, which might also be either a push or a pull, there are lunging and jumping actions which often relate to a squat, and there are leaning actions which could combine a twist and a pull, or a push and a pull on different planes of movement. But in broad strokes – push, pull and squat pretty much covers it. And if you base your training around this approach, it’s a simple way to ensure that your musculature remains balanced, and you can progress your strength in a symmetrical and harmonious way. I like to break it down one step further, because I find it useful for training – into the following categories: Vertical push Vertical pull Horizontal push Horizontal pull Squat (including jumping) Lunge or split squat When you keep it simple, you keep it applicable. You want your gym training to have a ‘real world’ application, and the more specific you get, the less applicable a method becomes. In general terms, if you’re good at pushing, you’re good at pushing. Being good at bench press or push-ups might not directly relate to being able to push a car, but once you’ve built up a degree of strength in broad strokes, you’ll notice it carrying over into other areas. Specialising in the triceps extension, however, will most likely have less carry over into other areas. The deadlift is always going to be a practical skill to train. What’s more functional than bending the knees and leaning forward to pick something heavy up off the ground? You might not always be grasping something as conveniently shaped as a barbell, but you can also train with sandbags, tyres and rocks if you like. And a deadlift looks almost the same as a squat - they do work slightly differently, but for beginning purposes, they can certainly be lumped in together. But one is a vertical push, and the other is a vertical pull - anyway, the subject of deadlift vs squats is is a topic for another time. To clarify: when you’re lifting a weight in relation to gravity, and the earth, it’s mostly going to be vertical in the gym, unless you’re pushing a heavy thing across the floor. By horizontal push, I mean horizontal in relation to your body. When you’re doing a push-up, in relation to the world and gravity, you’re pushing vertically – because you’re laying prone (face down) on the ground. But in relation to the body, we refer to it as a horizontal push because you’re pressing forward from the chest. Easy? The same goes for a bodyweight or inverted row. In relation to the world and gravitational forces, it’s a vertical pull, but because you’re laying face-up, in relation to your body it becomes a horizontal pull – the opposite of the push-up. You can combine planes of movement, or work in between the planes, as it were: an incline press is not quite a vertical or a horizontal press, but it’s a practical movement to be training. If you imagine you’re pushing a book case across a room, you’ll lean forward, maybe press one side forward from the other, brace the abs, and as you’re pressing – even if you don’t extend the arms, but you power it with the legs – you’ve got a kind of twisting, lunging incline-press going on there. To this end, the one-arm incline dumbbell press is a functional and practical movement to train. While pressing with one arm, the abs are braced against rotational forces, and you need to press the heels into the ground for stability and support. If we’re to look at basic strength development, we want our programming to be simple, with a broad application, and we want to be able to address our own personal weak points as they come up. This is what I find lacking in many systematised methods – sometimes too much specificity can be a bad thing, because it might not apply to an individual, and all the leg extensions in the world – personally I find them redundant. As with biceps curls, lateral raises – you can train them if you want, but if full-body practical strength is your goal, remember that these isolation lifts serve the big lifts. Use isolation exercises to bring up weak parts, and then continue to progress your strength in a balanced way. I favour an intuitive approach to training. This is for many reasons, but I notice that beginners will often respond quite well to pretty much any strength-development program. I don’t care too much about sets and reps and structure – this is where you come in. If you pay attention to what you respond well to, you can tweak your own program, you can choose whether you prefer to do more sets, fewer reps, many exercises, fewer exercises, you get to choose how frequently or not you train, for how long, how intensely, depending on what you find satisfying, that feeds your progression. Not much is really needed.  One arm dumbbell row - broaden the chest, arch the back, pull elbow to waist If you like variety, you can throw three or four different horizontal pulls into your training, or if you want to develop the coordination of a particular lift, and get a feeling for leverage and how much weight you can handle, you can choose one horizontal pull instead, and perform four or five sets. Have a rest in between each one, and see how you feel. Can you lift heavier? Do you want to try? Does the coordination feel efficient? Do you feel well-supported in terms of alignment? In your support muscles? Are you getting good leverage? Do your joints feel comfortable? Can you feel your shoulder blade moving, or is it stationary? How far can you extend, while still feeling strong? Do you want to lift lighter? Heavier? These are questions I still ask myself. If you want a balanced strength development program, I recommend the following: Warm up thoroughly. More to come about warming up in the future – but for now: your warm up should be something that you feel prepares you appropriately for the work at hand. It should not be too fatiguing but it should make you feel primed and ready to begin. Select one pulling exercise, one pushing exercise, and one squat based exercise. Start with the pull – it’s generally less stressful for your shoulders to pull than it is to push. Be aware that your first couple of sets are an extension of your warm up - you have not built up to the hard work yet. Continue with the push. Finish with the squat. You can practice a few sets of the pull before moving to the push and then the squat, or you can do one set of each exercise and rotate through, circuit-style. It’s up to you. As you get stronger, you’ll probably find you respond better to a few sets of the one exercise, with adequate rest periods, before moving on to the next exercise, than you do to training circuit-style. Sometimes as you get stronger, or as your ability to work hard improves, you’ll find you need to take longer rest periods. This might make you feel like you’re regressing, but it's actually a sign of progress. Pay attention to your body without judgement, but with an open mind. This is a very un-complicated way to train. I generally prefer to combine vertical and horizontal exercises the same way I pair pushes and pulls. They seem to go well together – for example, if I’m training shoulder press (vertical push) and one-arm dumbbell row (horizontal pull), I generally feel good, strong, and I can keep training in a satisfying way. If however, I choose a push and a pull both on the horizontal plane, or both on the vertical plane, like shoulder press and chin-ups, I seem to fatigue quicker, and it’s not so satisfying. Play around – see what you like. This approach will give you three big exercises that you can sink your teeth into, any or every time you train. You could design a satisfying and effective program that could look something like this: Day 1: Warm up One-arm dumbbell row One-arm dumbbell shoulder press (pictured below) Squats Perform s4 sets of 8 reps of each exercise, before progressing to the next one. Day 2: Warm up Pull-down or chin-ups Push-ups on the floor, or a bench, or with a weighted vest Lunges Perform 4 sets of 8 reps of each exercise, before progressing to the next one. Or if you want something simpler, that still works your whole body in a holistic way, you can choose one upper body and one lower body exercise, and just do them. You’ll get a satisfying but short training session in, and you should feel balanced and robust when you leave the gym – not having under or overtrained. You should feel like you’re ‘getting your moneys’ worth’, but you shouldn’t feel shattered. So let’s say – for a month or two – you alternate between these two workouts: Day 1: One arm dumbbell incline press (45 degree push – in between horizontal and vertical) Deadlift or squat Day 2: Pull down or chin-ups (vertical pull) Lunge or Bulgarian split squat If that was all you did, you could already build up a degree of strength, and certainly your body awareness and coordination would develop well too. As you progress week to week, you could change the angle of pull and push depending on how your body’s feeling. Some days might be more vertical-ish and some more horizontal-ish. Any assistance exercises you would select would be included in an attempt to bring up your weak points – not because of some vague idea – but because your body-awareness has improved, and you can start to become aware of what might be holding you back. But these exercises are included not because of some vague ‘you gotta do more, damnit’ propaganda – they’re chosen because they support your main lifts and your strength development over all. They serve the progression of the ‘big lifts’.  That might mean you add in some pullovers to support your chin-up progressions, some hip lifts to develop glute awareness and power and support your squats, or some prone holds/planks to help develop your ability to maintain body tension, which will support your push-ups. If you train in this way, there’s always an actual reason for your exercise selection – a reason for every repetition. It all relates to your progression. It’s the best way to stave off the brain-numbing effects of random, mindless training – make it specific and attentive. Pay attention to what you respond well to. ‘Junk’ sets and reps will not help you – don’t include anything in your training that does not serve a purpose. This will generally mean – if you’re used to training for sixty minutes, your sessions might suddenly be cut down to thirty minutes. This is fine. If you’re training for endurance, you’ll need to train for longer – but again, this is specific, not random – and if you’re training for strength, you don’t need to train for any particular duration. I will frequently throw in some extra training for the buttocks and upper back – because these are often weak points and can benefit from it. I will probably include some mobility work or stretching too, but that might be a topic for another time... There have been a few of them... Anyway a good, balanced session (with assistance work) might look something like this: Warm up Chin-ups Bench press Squat Reverse flyes or band pull-aparts Hip lifts with bodyweight only or added resistance (Please bear with my testosterone-injected links - the band pull-aparts clip in particular demonstrates great scapular retraction - the shoulders aren't lifting up around the ears, it's just solid upper back work, and it's a great shoulder mobility exercise too) Those last two assistance exercises could also be used as part of the warm up, and this work-out example would take about 40 to 50 minutes to complete and would make for a good session I reckon. It’s also worth considering the concepts of variety and consistency. If you train consistently, you can vary your exercises, and progress. You can train consistent lifts, but vary the weights and sets and repetitions. You will generally need to strike some balance between variety and consistency if you want to progress. This might mean a wide variety of exercises at every session, and that might stimulate you creatively, but you might not get enough repetitions of a single exercise in to feel that you’re developing your coordination and building awareness. It might mean practicing the same exercises every session for a month, consistently, which might lead to good coordination, awareness and understanding, but it might not provide enough variety to promote a broad application or carry over to other aspects of fitness and function – or it might not be interesting enough. Keeping training interesting is again about balance - it’s good to work on something that’s generally fun or rewarding to do, but you also need to be able to bring yourself to the task, knowing it’s not always going to be entertaining. Likewise, there’s a balance between structure and play – structure should serve you, it should not make you feel trapped. Structure should be on your terms, to help you work towards your own development, it should not serve someone else’s agenda. And if you want to just play, you can – it’s a wonderful way to learn about yourself – but if you want to progress athletically, structure will be helpful too. A balance of both will support a satisfying training experience in the moment that will help you to progress over time. And sometimes you’ll notice - especially if you have reason to be tentative or reserved when it comes to physical exertion - you might not need to do very much at all before you start pressing up against the boundaries of your capacity. Don’t worry. Don’t hurt yourself in the name of progress. As I’ve become stronger, my ability to dedicate myself to a single lift has increased. When I started out, doing 5 sets of 5 reps of one exercise would have bored me. Actually, when I started, I didn’t like (my impression of) strength training at all. One of the reasons I started with martial arts was so that I could get fit without having to set foot in a gym. But when I did finally get into dedicated strength training, I would do fewer sets, but I’d include a greater variety of exercises. But now, I can throw myself into training multiple sets of the same exercise, and it’s satisfying - I’ve been through processes - some of them conscious, some not so much. We often make the mistake of thinking that the way I’m training now, what works for me now, is the best method of all – not simply the most appropriate one for me at this point in time. Avoiding this delusion is key to keeping your training personal, and not getting in the way of your own progression by clinging to yesterday’s propaganda. If you follow your intuition, if you remain open-minded, curious and attentive, you’ll work out what you respond well to – physically and emotionally. If you pay attention to your coordination, leverage and progression, you’ll start to become aware of what might be weak points for you that require attention. And as you progress your strength - your capacity for hard work, your ability to train intensively, your understanding of efficiency and leverage – all this great stuff progresses too. That’s what makes it all so cool – you’re developing in many different ways, but all at once. We often miss that, in a culture that equates the success of a training program with superficial or aesthetic adaptations. It’s a shame, but anyway...

4 Comments

Michellers

9/5/2012 05:04:48 am

Thank you as always, Chris! I've been obsessed lately thinking about how to do just a few strength exercises every day and still be balanced and I love how your guidelines are both specific and loose at the same time. I'm still looking for a way to safely do squats without a gym membership/squat rack.

Reply

Chris Serong

9/5/2012 09:29:06 am

You're welcome! If you need to add extra load, one of the easier ways to do so is by wearing a backpack, or holding onto something heavy in your hands. But I suppose it's a knee/foot concern that's ultimately the worry? I was thinking about doing a post on squat-type exercises that you can do without equipment, and with that in mind I might spend some time talking about knee alignment... one of the easiest things you can try for naturally aligning your body is actually squatting down to a chair. Over time, you'd progress to a low step so the squat deepens, but if you actually have something to sit on, it seems to automatically help people sit the hips back and down (because you know where you're going), it removes the anxiety about falling, and helps you keep the heels flat on the ground. For knee and ankle health/comfort, you'd make sure your knees are pointing in the same direction as the toes, and possibly press them out to the side a little too. But if you're still getting knee pain when you try that, we might need to do some other exercises first....

Reply

Michellers

9/7/2012 01:03:44 am

I'm going to try squatting to a chair tonight...I'll let you know how it goes!

Chris Serong

9/7/2012 01:07:53 pm

Yes, please do! Leave a Reply. |