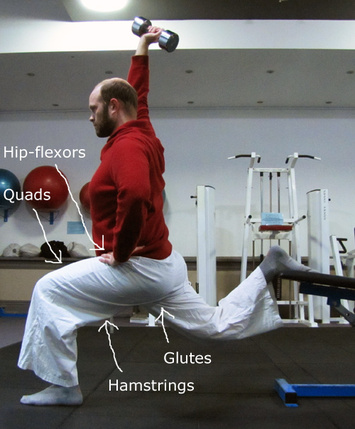

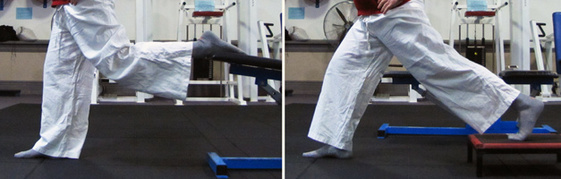

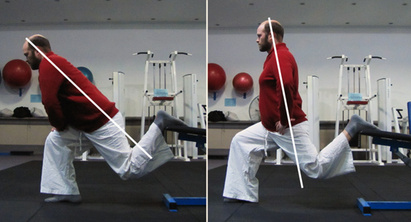

I’ve written about this exercise before, in broader strokes, but there are some finer points I was hoping to clarify. The Bulgarian Split-Squat is great for the buttocks and hamstrings, quadriceps and hip-flexors, for a few reasons. It stimulates muscles that often aren’t utilised for their potential to engage, and it stretches out other muscles that are often overworked or simply tight – but all of these benefits come down to leverage, angles and depth of squat rather than the exercise itself. If you haven’t read the first post, it might be a good idea to do so, but hopefully this won’t be too technically focused that it doesn’t make sense. To summarise, this makes for such a good postural exercise because it engages and exercises the glutes and hamstrings of the front leg, while stretching out the quads and hip-flexors of the rear leg, whilst under load. Why that is a good thing will hopefully become apparent. Of course, my first recommendation for anyone is always to do what they find helpful. This is an exercise, a technique, and as such it might be something you find helpful, or it might not. For many people it is too challenging to be helpful, and for others it is too easy. Never mind - your ability to squat does not reflect on you as a person, despite what some would have you believe. Training a muscle in an extended position, or stretching a muscle and then applying load, is a good way to increase flexibility because when you get a muscle to actually do something in an extended position, you’re not just stretching it out – you’re asking it to perform a function, and this leads to better adaptations as long as you don’t push it too far. The further you extend into a stretched position, the less you can load up a muscle safely. So everyone is in charge of the depth of their own squat. And for many of us, who don’t often move into a position of extreme hip extension, doing so can be quite difficult. It can also be quite emotional - the fetal position is comforting, and when you stretch the thigh back and open up through the front of the hip, when you reverse the fetal position, it can feel exposing and unsafe. If you’re training in an unfamiliar environment, it’s one of many things that can contribute to anxiety. But ultimately it can be good for you too, as long as you’re training on your terms. We are bullied into training far too often for my liking. Basically, this exercise – when taking leverage and coordination into account – supports hip mobility and helps to correct muscular dysfunction of the lower back. Tight hip-flexors and/or weak glutes - relative to your other muscles - often results in lower back pain and immobility, so the impressively-named Bulgarian Split-Squat is pretty much good for everyone... Unless of course you can’t do it, in which case there are other, easier exercises that can help. Maybe a topic for another time. On a different, but related note – we’re often told lifting weights will make us tight, but as with all things - it isn’t the weight itself, it’s how you train in relation to your own mobility. When I started squatting deeply with heavy weights, extending through my hamstrings under load, my front splits improved. I’ve never quite been able to touch down to the ground in a split, but when I built up the strength of my hamstrings in an extended position and then went back to training my flexibility, when practicing the splits I felt stronger, so I didn’t feel so vulnerable extending into my deepest split. I couldn’t go that much lower than before, but I could certainly get there a lot more safely. Anyway: the Bulgarian Split-Squat, or Lunge (with back foot elevated) – we’ll start with foot positioning of the back leg, then the front foot, and then work our way up the body.  Pointed foot on angled bench / flexed foot on flat step Pointed foot on angled bench / flexed foot on flat step The height of step you put your back foot on is entirely up to you. As is the choice to flex or point your toe. When I flex my toe and bear my weight on the ball of my foot, I find this places a little too much tension on my instep knee, so I prefer to use a higher, angled bench and point my toes. Try to make sure you’re pressing the top of the foot into the step, but don’t let the foot roll out to the side too much. You still want it to stay straight. This should transfer pressure from the knee higher towards the front of the hip – where we want it to serve the hip-flexor stretch. If your foot is flexed, try to apply even pressure through the ball of the foot, and don’t let the ankle roll out or in. The foot should be facing straight forward, with the toes and heel aligned with the knee, not out to the side which only applies unwanted pressure to the ankle. This position already requires a degree of flexibility and strength in the ankle joint, and so, a pointed toe might be better. The position of the front foot is determined (again) by your flexibility. At all times, your front heel should be pressing into the ground. If the heel lifts off the ground, or even if your body’s weight moves forwards to your toes, this will make it harder to balance. If your stance is too narrow, the knee will come forward beyond the toes, and this will move the workload into the quadriceps rather than the hamstrings and glutes, so again it’s all about leverage. Likewise, if you don’t squat down very far, you’re not giving the glutes and hamstrings an opportunity to work. If you lean the torso forwards and lunge only slightly, it’s just going to be a front-leg quads work-out and isn’t going to deliver the benefits this exercise is known for. So your foot needs to be far enough forward that when you’re down in the bottom position of the lunge you can still drive through your heel – you don’t automatically shift your weight forwards – but if your foot is too far forward, it’ll limit how deeply you can lunge. For balance, foot stability and strength, I recommend training in fairly minimalistic footwear. If you’re not able to train barefoot, and many of us aren’t, try to use something flat-soled, that allows you to have an actual tactile experience of weight distribution through to the ground. Many companies make barefoot-inspired footwear these days, but an older-styled pair of Chuck Taylors or Dunlop Volleys or simple flat-soled canvas sand shoes are much cheaper and will serve your purposes perfectly well.  Flattened arch: knee collapses in / lifted arch: knee pulls out for better leverage Flattened arch: knee collapses in / lifted arch: knee pulls out for better leverage When you remove the technology of sports padding in footwear, you can feel where you naturally are inclined to collapse, and you can feel your arch, and all the little muscles working. This can be a bit tricky, because your muscles are working against each other, but try to imagine if you can that you’re pressing the ball of your foot into the ground, while also pulling up through the arch of your foot, and pressing your heel into the ground too. When you press the inside edge in particular of the ball of your foot down, it helps you to stabilise. When you lift up the arch, it helps you to develop strength in your feet, and it helps to pull the knee out where there’s less chance of it collapsing in – this is a better position for leverage and stimulating gluteal activation. And of course, when you press your heel down, you’re much more grounded, able to squat deeper, and your balance will benefit remarkably. So in the one foot, you have two clear points of pressure, and one point of pull in between them. Clearly there are a lot of things to be aware of in the action of the front foot alone. The front knee, as I mentioned, should be pulled slightly to the outside, this feeling and the feeling of lifting the arch are linked. It’s the glutes that stop the knee from collapsing inward (or, to be more specific, the femur from internally rotating), so if you cannot keep the knee straight or pressed slightly out that’s okay, there are other things we can do for the glutes. Whether you think of lifting the arch, or you think of engaging the glutes to keep the knee from collapsing in, might not make much difference. You can come at knee alignment from the feet or the hip, depending on you. This is a point I’ve been paying more attention to in my own training, but what helps you best might not be what helps me best. If the torso and the shin of the front leg stay vertical, this will serve you best. If you feel a pinch in the lower back, you might be resting the back foot on a step that is too high. The back will pinch and compensate for tight hips by arching excessively as you try to keep the torso vertical. Lower the step until you have developed your hip mobility/flexibility some more. You can also squeeze the abs to brace the lower torso – whatever works to stop your lower back from feeling like it’s collapsing or arching too much. But oftentimes – rather than select a lower step or exert more force to brace consciously – people simply lean forward and don’t observe the changes in leverage and muscle activation, and so they miss out on the strength and mobility benefits, and ultimately won’t progress as far as they could otherwise.  Forward lean: hip stays closed / vertical torso: knee is behind the line of the body Forward lean: hip stays closed / vertical torso: knee is behind the line of the body You’ll notice when the torso stays vertical - in relation to your body your back knee extends behind your hip at the bottom of the lunge. This is where you will feel the main extension in the hip, and if you’re being a bit too ambitious, it’s also where you’ll notice the lower back pinching. You’ll also notice if the body leans forwards and the weight comes forwards that the rear knee no longer extends behind the hip, and you lose the hip-stretchy-benefit. The front glute will stop working so hard, and the lower back muscle and quadriceps will be responsible for muscling you back up to the top. A tight lower back is often a sign of weak glutes, so this will not serve us, it will only be a bother. As the glutes fatigue, you will often notice when lunging that people cease to rise with a vertically aligned torso - instead they start to lean forwards, straighten the legs, and then straighten the body up the top. It becomes a two-movement, hip-swaying lunge: legs then back. This serves no particular purpose - if you cannot keep the body vertical, then the glutes are done. Rest and repeat when you like, but if you push through when the muscles you are trying to train are fatigued and unresponsive, then you’re only training poor movement patterns. And I don’t give a damn how many calories you’re burning, athletic progression is about specificity, movement efficiency and the development of power. You don’t get that by compensating with your lower back, and burning calories has exactly zero relevance when it comes to athletic advancement. As a little aside, the terms ‘weak’ and ‘strong’ are strictly to be used in a relative sense, free from judgment. A person may be weak or strong when compared to other people, and your glutes may be weak or strong when compared to your quads. Any person may have a well- or poorly-balanced musculature, but it doesn’t reveal anything about your character or worth, so y’know – whatevs, dude. Work on what you want to work on. I’ve been using the terms ‘relative’ and ‘absolute’ much more frequently in life – I find them quite useful. Your relative strength has to do with muscle balance and strength in relation to your own body, while your absolute strength has to do with the actual number of kilograms you can move. Hence, push-ups and lunges test your relative strength, while picking up a 20 pound dumbbell and lifting it for numbers tests your absolute strength. Maybe, for me, it’s just another way to strip away levels of judgement and prejudice. There are different types of strength and power. What’s meaningful for your progression? So – if when you lower into the position, you feel a stretch in the hip-flexors and quads of the rear leg, you feel your knee joints are comfortable, you feel the hamstrings and glutes of the front leg working for balance, power and stability, you don’t feel your lower back pinching, you can keep your chest up without leaning forward, and you can press your heel and the inside edge of the ball of your foot into the ground, while lifting through the arch, if you can be aware of all this, you’re doing really well! Hooray! If you can, hold this bottom position for a heartbeat (experiencing the stretch and tension) before squeezing the glutes of your front leg and pressing back up to the top. Adjust your foot-positioning if need be. When you reach the degree of strength, coordination and awareness that you can practice this movement for multiple repetitions without losing balance, we can start to talk about further progressions, which can be as easy as holding onto dumbbells, changing the height of the step, leading into small jumps with the front leg, or extending one arm up above your head. More to come, dear readers, more to come. But there’s no need to rush. Work within your capacity and challenge yourself as you like. Muscles adapt faster than ligaments, tendons and joints, so pay attention to your joints, pay attention to where you’re feeling the stretch and tension, and adjust as need be. Related posts: Deep Squats And Hamstring Flexibility (Part One) One-Leg Pistol Squats And Hamstring Flexibility (Part Two) (Edit: 19 June 2014) Also, this is a great article, all about cueing the position of the knees, and how the foot, ankle and knee interact with each other through the shin bones. It contradicts much of what I have learned so far, but in a good way, and although it still leaves some questions unanswered, it's well worth reading, especially if you experience any foot/ankle/knee problems when squatting.

5 Comments

david

10/18/2012 01:32:27 am

I lifting half my body weight with a plated barbell. I've raised by front foot to get my front thigh slightly below parallel. I am obsessed with strenthening by glutes. What about raising back foot very high? Difficult to maintain upright posture and range of movement is less but is it good for the glutes?

Reply

Chris Serong

10/18/2012 08:55:26 am

Thanks David. In general, a deep range of movement is good for the glutes, so yeah, you don't want to sacrifice range of motion too much. When I'm doing this technique, I notice a tendency for the quads to take over in the upper part of the movement if I'm not focusing on pushing the heel down. The best thing I always found for the glutes is really to focus your attention on them throughout the full range of motion, and apply leverage through the heel - in some parts of the movement you mightn't feel them very well, and it took me ages before I really felt like I could feel them working in the bottom position, where they're most deeply extended, but deepening my concentration over time has been very helpful.

Reply

david

11/18/2012 03:49:45 am

Thanks Chris. Focusing on the glutes is not easy, is it? I find it so hard mentally to concentrate on the muscle and in other sports I have good visualization skills. Depth/ROM and heel anchor and upright posture awesomely importart. Every homosapien should do some form of squats.

Reply

Chris Serong

11/19/2012 11:55:50 am

No, it's not easy! I find the closer you get to vertical, and the more you focus on pressing the hips forwards, so you're pressing the hips open at the top, rather than just standing up, the more you can feel them. But that works better for deadlifts and squats than it does the split squat, I think. And if your hip is extending, you're using them to a degree, even if you can't feel it - so at least there's that.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |