|

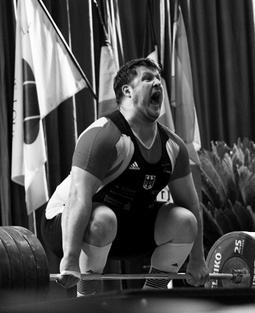

The reason we include exercise in our lives is to make our lives easier or better in some way. It’s not because we have to, that only leads to resentment, it’s not because of obedience – or when it is, our efforts are frustrating and short-lived. When you are coerced or manipulated, of course it doesn’t work out in the long run; there’s nothing wrong with you when you rebel against emotional manipulations. Sometimes it’s right not to play along. Exercise makes your life better when you do it on your terms. And so it is simple: exercise makes life better. It makes your life easier, that is why we do it. And if it’s not, then you need to reassess.

5 Comments

You might have heard of Tabatas, or the Tabata Protocol. It’s a high-intensity method of cardiovascular conditioning. People talk a lot of shit about it. Essentially it amounts to 20 seconds of all-out super intense exercise followed by a 10 second rest, and you do that for 8 rounds, which is a total of only 4 minutes. It doesn’t take up a lot of time. People misrepresent the protocol frequently – it’s not for strength training, it’s not for biceps curls or crunches, it’s for full-body cardiovascular exercise, but many things are misrepresented these days so that’s nothing new.

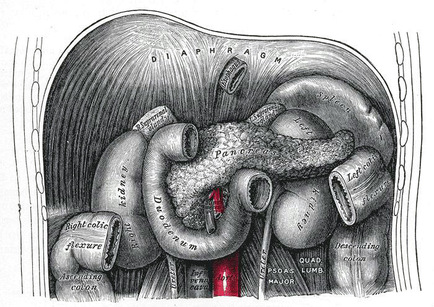

Of course people use this protocol in an attempt to lose weight – we use all kinds of exercises to that end – but it might need to be said that Izumi Tabata, the scientist after whom the protocol was named, at no point in the study paid any attention to fat-loss or body composition. Anyway. What interests me is the topic of insulin sensitivity, or to frame it more practically, your body’s ability to assimilate, utilise, or metabolise carbohydrates.  - for the injection of insulin - - for the injection of insulin - The fear is that fat acceptance is bad for diabetes, that it might lead to more cases of diabetes – that if I don’t hate and fear fat, I’ll become sick – but it’s total crap. As if being afraid of fat keeps us healthy? It’s rubbish. The truth is that fat acceptance and body positivism are good for people with diabetes, and here’s why: I have become aware of certain dangerous behaviours. There is a tendency with diabetics who have body-image issues, to let our blood sugar levels run too high – to inject only conservative amounts of insulin, because insulin “makes you hungry”, and we all want to be thin. We think we need to eat less, because we think we are too fat. If you are currently thinking that you, yourself really are too fat, you are wrong. Sorry. And anyway, eating less doesn’t make you healthier, and it doesn’t make you thinner, so fuck it all.  I say it a lot – it’s okay. And it’s because I believe it is. We are all okay. Humans have an incredible capacity to both deal with suffering and get on with life – doesn’t mean there’s no trauma – but judging yourself for having to endure trauma – how helpful is that? Judging yourself to be damaged, or un-okay in some way – is that helping? And saying that it’s okay – does that invite procrastination? Or does it encourage convalescence? I don’t believe self-acceptance is the enemy of self-development. It’s a prerequisite. I’ve got type one diabetes, I’ve had it for 20-plus years, and I’m okay. My kidney function is great, my eyesight is great – I’m sick, and I’m okay. And if I were sicker, is that okay? It might not be okay, I might not be okay with it, but I’m still okay. Being sick does not make you a failure as a human being. We fear it, but that’s something else. So is it okay for you to be obese and healthy? Or at least obese and not-sick? Absolutely. It’s okay, and you’re okay. It’s okay because mortality and sickness is something everyone is going to have to face at some point. It’s okay, because it’s okay for humans to be human. And death and sickness are part of what we have to deal with in life. So it’s all okay. Bleak as it might sound, everything is as it should be.  The fear of fat can be interpreted as a fear of chaos (because fat acceptance acknowledges that some things exist outside our capacity to control), a fear of disease, or a fear of being socially ostracised. I think the last point is oftentimes the most powerful and immediate one, but it’s obvious so I won’t elaborate. Really all three fears boil down to the same thing: the fear of chaos and inevitability. You cannot embrace fat acceptance without considering the notion that one day you’re going to die, and you cannot put a stopper in death. No wonder people rage against it. We cling to the notion that fat can be controlled, and we cling to the notion that health can be controlled, and we cling to the notion that fat causes disease because if all that is true, maybe if we can stay thin we can buy the lie that we’re safe, that we’re not going to get sick, and maybe – not today at least – we’re not going to die. We’re not too naive, we know we can’t stop it, but as long as we don’t get fat... Maybe just...  The Pancreas: Maker of Insulin (among other things) What they don’t tell you about diabetes is extensive. What we don’t know about diabetes is more so. I haven’t written as much about my experiences with diabetes as I thought I would, but I have a few things in mind – unique observations that I don’t hear people talk about very much, as it were. There are many misconceptions about diabetes. I have read two separate articles lately (here’s a sciency one and here’s one from the press) that indicate overweight diabetics fare better than thin ones – and when you start talking about what that might mean, people are quick to shoot you down. Maybe that’s why it was always so hard for me to lose fat – maybe there was a reason for it to be there. Anyway. Something that took me twenty years to realise that nobody tells you is that the same foods affect you differently depending on where your blood sugar’s at. This shouldn’t be revelationary, because the idea that the same food has a different effect in different circumstances is far from new, but we’re always told “this is how it is, peasants”, and then we’re told off for not taking personal responsibility when we’ve been badgered to do exactly what we’re told. This is a follow-up post about insulin resistance, obesity and diabetes. You can read the first part here. In the interest of being clear, and not over-simplifying the matter: being obese won’t give you diabetes; there’s a mechanism to it and many interrelating factors. We are sold fat-fear and propaganda in the name of health, but what’s actually good for you, what’s practical and achievable is a little bit different.

Although obesity doesn’t cause diabetes directly, the association with insulin resistance and obesity needs to be addressed, which is where it gets both tricky and interesting. When it comes to insulin resistance – in and of itself – that’s not enough to give you diabetes. And even if you are insulin resistant and obese, that doesn’t mean you can’t do anything about it, because exercise – almost any sort of exercise – dramatically increases your insulin sensitivity, even if it does not result in any weight-loss whatsoever. Why, when we start to exercise, do we think that the ‘exercise isn’t working’ if we ‘fail’ to lose weight? So what if you aren’t getting smaller? The question I’m asking is whether or not that matters, and if so, how much?  Big and strong. It's not just a saying. An internet search for fat acceptance will yield a lot of good reading, and a whole pile of hate-filled results. People ask if it’s really possible to be healthy and fat, but in my current slightly cynical frame of mind, I find myself asking if it’s possible to be healthy and thin? Thinness is not a protection against disease, and fatness does not seal your doom. Fitness trumps body size every time and I've often seen fat acceptance blamed for increased mortality - in relation to deaths that weren't even caused by being fat in the first place. So what gives? Obesity is popularly associated with all kinds of diseases, particularly diabetes, but let’s take a look at the mechanisms for a moment: Type one diabetes is an autoimmune condition. Your immune system malfunctions, and your body mistakenly identifies certain pancreatic cells as foreign matter and starts to attack them. After this onslaught, the pancreas is no longer capable of producing insulin, so injections of insulin are therefore required. |