Stretching is to flexibility training, what doing a workout is to strength training. Which is to say, any one session may feel good, you can lift a weight and do a stretch and it will feel satisfying, but any single training session in isolation is kind of meaningless. I don’t mean to be a hard-ass about it or overly pessimistic. When you’re calorie-obsessed, yeah a workout that burns a lot of calories will feel useful, but if you want to progress in some way, if you want to change the condition of your muscles or body, of course it’s the accumulated benefit of your training that has meaning. But we’ve all been told before that a workout here or there means nothing, we’ve all been told consistency is key, and then we’re usually shamed in an attempt to inspire our sense of commitment. What’s the endgame to that, really? The only way to commit to something without burning your soul in the process is if it’s something that’s meaningful to you. If you both care about the endgame, and you enjoy the process, then you’re on a winner. You may work hard, but it won’t be hard work turning up. And often the progress that is meaningful to us is meaningless to others. They will ask why do you dedicate your efforts to this thing? Why do you stretch if it won’t make you thin?

1 Comment

The reason we include exercise in our lives is to make our lives easier or better in some way. It’s not because we have to, that only leads to resentment, it’s not because of obedience – or when it is, our efforts are frustrating and short-lived. When you are coerced or manipulated, of course it doesn’t work out in the long run; there’s nothing wrong with you when you rebel against emotional manipulations. Sometimes it’s right not to play along. Exercise makes your life better when you do it on your terms. And so it is simple: exercise makes life better. It makes your life easier, that is why we do it. And if it’s not, then you need to reassess.

The plan is to create an exercise library of sorts, featuring weightlifting techniques and information, Tai Chi and Kung Fu tutorials, clips of me just messing around, and more. So my YouTube Channel should grow slowly over time.

There are two primary approaches when it comes to structuring a strength training program: one may choose to prioritize volume or intensity. Usually it’s not possible to do both, although you may work very intensely while training with a great deal of volume. But that assumes you’re kinda advanced already. To clarify: To take a high volume approach, you would focus on getting many, many high quality reps into your session, but you wouldn’t train until failure. If you prefer the high intensity method, you wouldn’t be overly concerned with the number of repetitions, instead you would focus your energies intently on only one work-set, and you’d push as close to muscular failure on that one set as you could. The goal is one intense experience per exercise. There are pros and cons to each approach. The way to get better at a thing is via feedback. Feedback, unlike criticism, can come in many forms, and is absolutely necessary if your goal is to improve at a thing. My Kung Fu and Tai Chi students sometimes struggle to practice, because they lack confidence that they are practicing correctly.

We often mistake a lack of confidence for laziness, and wonder “why can’t I bring myself to this practice? What’s wrong with me?” and we find ourselves doing something else, even when we have the time to practice. Mostly I think, it’s about not quite knowing what to do, feeling adrift, or unsure of ourselves. We question our own methods and motivation, and on some level it’s very easy to wonder what is the point, if we’re not training rightly? This is one of the ways in which perfectionism can really get in the way of, well, everything. A Tai Chi teacher I know recently said that the belief you should be doing it perfectly is the number one reason why people don’t practice, especially beginners. Oftentimes just trying to add more reps doesn’t quite work. It can, in the long term, but day-to-day, it can also feel kindof pointless and frustrating, depending on what you’re working on, and the mentality you bring to the task.

If you want to progress your chin-ups, it’s true that you’ll need to work hard, but it’s better to work at something useful, something that gives you a sense of progress, and to that end, there’s probably something more useful you can do than stubbornly try to muscle through something that isn’t quite working. My usual approach to any technique or exercise is this: identify the weak spot, find exercises that target it specifically, train them, and then in time test your methods by training the original exercise again. See if the weak point has shifted or improved in some way. I think it’s good to remember that what you are testing is the effectiveness of the training methods you have employed, not your worth as a person. If the test fails, then the training methods were ineffective. That’s where the problem lies – there may not be a problem with your work ethic or personality. Instead, it’s just that the training methods did not work for you. Were they poorly prescribed? Did you work too hard or not hard enough? Were the assumptions off? Do you simply need more time or patience before your body can adapt?  It always amazes me how strict people can be about rest periods. Here’s the thing: you can’t get it wrong. Sometimes people say you shouldn’t sit down, and they’re quite insistent. Keep standing, keep moving, keep your energy up – and there is a benefit to it, it’s about intention. But it always depends on what you’re doing. And not every workout is about psyching yourself up for some crazy intense training. Often, we might bitch about how other people spend too much time on their phones at the gym. But if you’ve just done a set of leg press or whatever, I don’t care if you check out all the dinners your friends have been sharing on facebook from the night before, while you recover enough to be able to do another set. And who cares, really? What is the point of resting? Recovery. So you can do stuff again, and do it well. Think about what you want to achieve. There’s a difference between what is easily measurable and communicable to a population, and the essence of effective training methods.

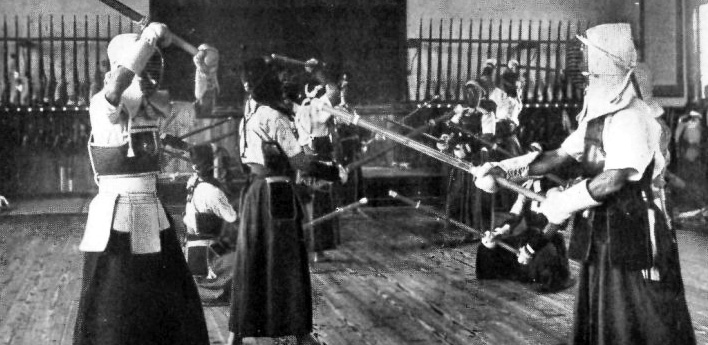

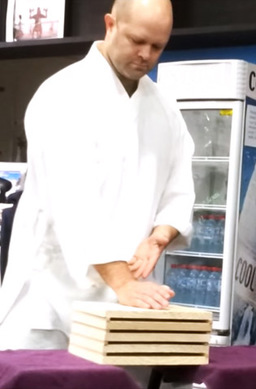

Science is observational, and as such – the task is to try to interpret the essence of a thing. What we learn from observation then needs to be communicated – this may happen via scientific journalism, or it may trickle down through various levels of social media and rumour. Much of modern gym training comes watered down from bodybuilding, powerlifting, and other sports. Sometimes also from studies, from research in the field of sports science. But there is much that occurs in the lab, in experiments, and in sports that cannot be easily measured or clearly communicated.  I’ve spent the last few months teaching one of the other personal trainers at work how to break wooden boards with her hands. The other day, we held a small demonstration, footage of which can be seen here. And on that day, I had three people ask me what the trick is. I said training, and conditioning the hand over time, and understanding appropriate progressions. I also pointed out that it’s easier with certain striking areas than others, but that is simply an aspect of understanding the nature of appropriate progressions. Now that I reflect upon it though, I think the question reveals something else that’s going on in the fitness industry. Of course there is no trick. It’s just training, conditioning the body, and developing over time. The two primary keys to progress are of course known, they are patience and consistency. Moving forward to what will be helpful when it is helpful, but not before. Avoiding injury, over-stimulation, boredom or stagnation. The easiest way to break a board is with a muscular – rather than bony – surface area. So of course we begin by practicing the correct technique and leverage, and getting the heel of the palm used to a small degree of impact. Over time, one may progress to striking with the knuckles, but of course – while stronger in a certain context, the knuckles are also more fragile and vulnerable to injury. So again, appropriate steps only. Move from the simple to the complex, what is doable to what is challenging. People sometimes wonder how frequently they should train, and we often overcomplicate it. Train again when you’re ready, do not train when you’re not.

There is no one correct answer because there’s an inverse relationship between intensity and frequency. The more intensely you train, especially with weights, the longer it takes for you to recover. Hence you cannot train too frequently. Likewise, if you train especially frequently you will probably find you are not capable of performing high quality work at the degree of intensity you might expect, but you may be capable of practicing low-intensity endurance or mobility work. |