|

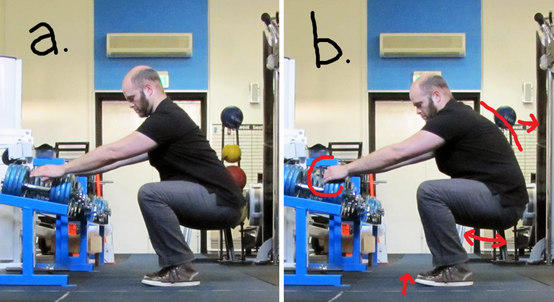

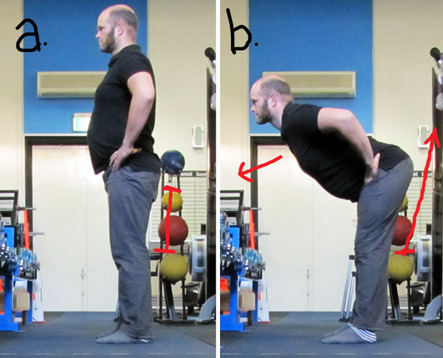

People often think the key to squatting deeply is calf and achilles flexibility - especially when they think of the pistol squat - but even though it might feel like that's your limiting factor, it's hamstring flexibility that usually holds you back. In the above pictures: the standing, half-squat, and full seated squat, you'll notice that the knee doesn't project much further forwards than the toes. The difference in the angle of your lower leg between a half- and full-squat is not all that much. The heel remains flat on the ground, and as you descend, with the knee joint remaining relatively still in space, the stretch that the calf and achilles are under does not really increase too much. Hamstrings, however, is where it's at. The hamstrings connect the back of the knee to the 'sit bones' of the pelvis. If you try to keep your back vertical with your spine in neutral position, this requires you to maintain a kinda flat pelvic alignment. The more you sit your hips back and down, maintaining this pelvic alignment, the greater the distance between the knee and sit bones. Thus the hamstrings are lengthening. Even though it might not seem that way.  The corker is the bottom position. Or even the half-way position, depending on you. If the hamstrings are tight, the sit bones cannot continue to move away from the knees, so the hips tuck under (picture b), which rounds out the back, and moves your center of gravity backwards, away from your feet - so either you fall or you have to hold onto something. Because you sense pressure coming away from the balls of your feet, people often think it's a problem of the calves being too inflexible. But if you can get your knees above your toes, while keeping your heels flat on the ground, your calves are actually fine. The advantage to squatting with both feet on the ground is that you can lever the feet and legs against each other for stability and traction, and you can squat in between your legs, rather than kinda over the top of them. You can fudge the angles a bit to suit you. Part two of this post will focus on the one leg pistol squat, which is significantly harder - obviously loading is increased when you're doing a squat on one leg only, but you also can't squat down to the side of your leg, and you can't really lever against anything else to help stabilise the ankle, knee or pelvis. When you pull the knees apart, it engages the glutes, which stabilises the pelvis. Many people with knee pain find they can comfortably squat if they follow these cues: Weight on your heels Press the big toes into the ground Pull the knees apart Break at the hips Sit the butt back as if you’re sitting onto a chair, or Squat in between the legs Press the hips forwards to stand, rather than thinking of moving the body upwards It’s not uncommon to get halfway down and realise you’ve already forgotten to keep pulling the knees apart. This is fine, it’s all practice. But many other people still find that’s not enough, because knee dysfunction can be caused by a whole bunch of different things. Ultimately though, building up the strength and flexibility of the hamstrings and buttocks can go a long way to preventing and resolving lower back and knee pain.  One of my favourite hamstring stretches in this context, is to simply lean forwards from the hips. You do need to arch the back, and keep the chest up, because you don’t want to be compensating with the back. The intention is – as the body leans forward – to lift the sit bones up towards the sky, away from the knees, lengthening the back of the legs. Rounding the back forward only distracts from the hamstrings, whereas holding that natural lower back arch, bracing the abs, and leaning the torso forward – hinging from the hips, rotating the pelvis – that creates the right sensation in the hamstrings. That’s what it’s like to lower down into a deep squat, as far as the hamstrings go. Hold the stretch for as long as you can – up to a minute or two if you like – and try to focus not on tension, but on relaxation. As the hamstrings relax, you might be able to sink a little deeper. Do so, and repeat for as long as is comfortable. PNF or contract-relax stretches might also be helpful, but for now – if you relax into it, it makes for a good sensitivity and awareness exercise too, where you’re really focused on the legs. Then, when you go to squat again, see if you can identify that same feeling as you sit the hips back and down. You’ll know when you’re at the extreme range of your hamstring flexibility, because the pelvis will want to tuck under. Keep the lower back arched, or at least flat, and brace the abs – when you can feel the lower back starting to flatten and then round out, that’s your hamstrings pulling on your sit bones. If you’re not lifting heavy weights as you squat, it doesn’t matter much if the hips tuck under or not. Just as long as they don’t tuck under so far that your back rounds out enough to pull you over. For safety purposes, maintaining that flat back will protect your spine if you’ve got a barbell on your shoulders, but there are also advantages to working through that hip-tucking point without extra load, and observing what happens in the lower back and glutes and hips when you do. Read Part Two.

5 Comments

Lucas

12/4/2014 12:52:05 am

Hello.

Reply

Chris

12/4/2014 01:47:21 pm

Hey Lucas,

Reply

Chris

3/6/2016 06:42:56 pm

Ha! Calm is not how I describe my experience of squats.

Reply

Jane

12/4/2016 03:02:59 pm

Thanks,

Reply

Leave a Reply. |