|

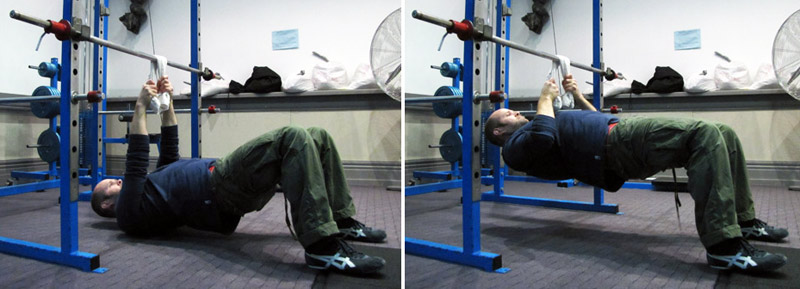

Firstly – to touch on the horizontal pull-up in a little more detail: there are two main ways you can do this, and a bunch of variations. Method one: when you pull your body up to the bar, you aim to bring your nipples or lower ribs towards the bar – your hands are placed around shoulder width or a bit narrower, and this will place most of the emphasis on your lats and mid-back. Method two: when you pull up towards the bar, you lift your chin or neck towards the bar. The hands are placed wider apart, so at the top of the movement your forearms are exactly vertical, with the elbows straight underneath your wrists. This places most of the emphasis on your upper back – the scapular retractors, shoulder muscles and trapezius. Both methods are useful, and you can always vary your training to suit your body. Variations include bent legs, straight legs, elevated legs – pronated, supinated, or mixed grip – and using a towel for challenging your grip. If you aren’t very strong at this exercise, squeeze your buttocks and really drive your heels into the ground to maximise on leverage through your legs. It’s a great exercise for a whole bunch of reasons. However, if you feel a pinch in the shoulder when you pull up to touch the bar, don’t go so high. Shoulder flexibility can be an issue for a lot of people, and if you’re tight through the chest and front of the deltoids, pulling all the way to touch the bar might simply be bad for your joints – but you might be fine, and it might be useful if you pull up until you’re a few inches away from the bar.  Wide hand-placement; mixed grip Wide hand-placement; mixed grip You can make it a mighty grip (and abdominal, and scapular) exercise if – instead of pulling your body up through space – you keep your arms straight, have your legs placed wide apart, brace one arm and imagine you’re locking your shoulder blade into your ribs, and then your other hand – you slowly let go of the bar. Squeeze the hell out of the bar with the hand that’s still holding on, focus on pulling your shoulder blade into your ribs, and make sure you don’t let yourself fall. Programming: Once you’ve become confident and familiar with the various techniques, if you like, you can start to take a more focused look at how you progress your training over time. So far we’ve covered various techniques including: Squat-chin and jumping-chin; Pullovers; Scapular pull-down or chin-up; Grip exercises including barbell wrist curls, towel curls, farmers walks and the wrist roller; And we’ve touched on the horizontal pull-up. I’d prioritise the actual chin-up movement – jumping or otherwise, farmers walks (a heavy carry is more relevant in chin-up-grip-related terms than wrist flexion or extension), the horizontal pull-up, and the pullover above the other exercises. You can rotate through the main exercises as you like: one session could be all about the chin-up movement – jumping or controlled negatives or whatever – and another could be all about the horizontal pull. The pullover and grip exercises work better as ‘assistance exercises’. If you’re training at a gym, of course, you can prioritise the pull-down machine, the assisted chin-up machine, and you might have access to a band so you can do band-assisted chins. Also, once you’re familiar with the exercises, you might notice you get to a point where your progression has really slowed down. When you are just beginning, strength improvements can be more rapid – a lot of progress is made by building up the brain-nerve-muscle connection. But when you’re focusing on a particular exercise, you always reach a point where progress stalls. One of the best things you can actually do is take a break from that movement pattern – give your body a break, and focus on something else. So it can serve your progress well if you can give yourself a month or two where you focus on building up your chin-ups, or in general terms your pulling strength: chin-ups, deadlifts, rows, rope pulls, dragging heavy things. Then give yourself a month or two where you focus on building up your pushing strength: handstands, push-ups, pressing heavy objects, dips. You don’t need to completely exclude pushing when you’re focusing on pulling – instead, it’s your focus that shifts. This way you have the best chance at avoiding boredom, overtraining, joint imbalance/dysfunction, etc. I find when I’m training, it’s helpful to rotate my primary focus through the various lifts that interest me. It’s simply more stimulating. Variety is the spice of life, and if you’re still training most of your body one way or another, you don’t actually need to worry about your bench press dropping off if you don’t touch it for a month. Some push-ups and shoulder press here and there will keep you from losing touch, and taking extended time off is often really good for recovery. And of course, if you are focusing on alternating between periods of pushing and pulling, you’re continuing to build your overall upper-body strength, without overdoing any one exercise or movement pattern. And overall strength is great. I think chin-ups actually have more to do with overall strength and joint function, good movement patterns and leverage, than they do the strength of specific muscles like the lats or biceps. This is why building up your push-ups can have a positive carry-over to chin-ups. Depending on you, and where you’re at, you might like to focus on pulls for a week, pushing for a week, and alternate that way. Or you could do three weeks of one, take a week off, then three weeks of the other. Or you could spend two to three months on one or two exercises, if you feel like you’re getting something out of it. But when it starts to get laboured, if you start to feel fatigued and like you’re really struggling to grind through your training, don’t just blindly forge ahead – it’s not useful. Don’t judge yourself or your progress, simply try to pursue what’s actually useful. Enthusiasm is an important guide. If you start hating training, it can be a sign that your central nervous system needs a break. You might just need time to recover, and this is not a sign of weakness. Being respectful of yourself and your capacity is essential if you ever want to exceed your capacity. You need to stimulate your body, not just grind it into the ground. Training until failure all the time proves nothing – but if you’re anything like me, you might need to be stuck in a couple of months of tiresome, uninspired-exercise-to-failure-routine before you work that out for yourself. We need to focus on what serves you. If you are dedicated and committed, if you are able to – and enjoy – training hard, then if you’re not progressing the usual approach is to try to train harder. But you really do get to a point of diminishing returns from this method. Discover when it’s helpful to change your approach. It’s also great to give yourself helpful cues. An example of an unhelpful mantra for me would be “come on, you’re useless, lift yourself, damnit! Stop being a weak bitch!” – I’m not down with policing my own oppression. I’m not into relying on negativity and worthlessness to keep myself motivated. If you are into that, it can be confronting when you consider changing, because it’s the only way you know. If I’m not hard on myself, how will I get myself to train? You will need to change your value system. What do you value? Why do you train? Why are chin-ups important to you – do you believe your worth is determined by your strength or ability? Because it isn’t. That’s only a popular lie. If the only way to get yourself to the gym is through self-abuse, you simply won’t believe that some people go to the gym for fun. If all that’s important to you is being thin, if the gym is only a constant reminder of your perceived inadequacy, of course you won’t find it any fun. So don’t blame yourself for not liking this thing that everyone else says they like. I find training more enjoyable, the less I value thinness. It’s freeing. It’s all about perspective. Helpful visualisations and mental cues include: Lift your chest towards the bar, not your chin (for the chin-up, not the horizontal pull); Pull your elbows to your waist or ribs; Squeeze the bar; Arch your back; Open the chest; Pull through the shoulder blades. Remind yourself of what’s helpful to you. I find it most useful to think of bringing the chest to the bar and the elbows to the ribs. That locks my spine into the right position, even if my chest doesn’t actually touch the bar – it doesn’t need to be literal, it’s a visualisation. If your neck or chin clears the bar that’s far enough. Some people don’t have healthy enough shoulders to pull all that way without pain, even if they are strong enough – it’s the same as the horizontal pull-up.

4 Comments

9/30/2013 06:50:04 pm

Very knowledgeable post. Currently i do reps and triceps little bit coz i have muscle spasm. so do you think that horizontal pull ups are safe for me?

Reply

Chris

10/1/2013 03:09:39 pm

If they don't cause you pain, they're probably safe. But if you're getting muscle spasms you need to look into your muscle recovery, nervous system, nerve health, etc. Consider taking magnesium - consulting with a health care practitioner is best.

Reply

2/24/2021 01:05:24 am

Informative post about horizontal pull-ups. Thanks for sharing.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |