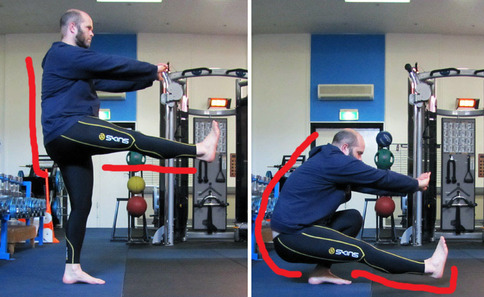

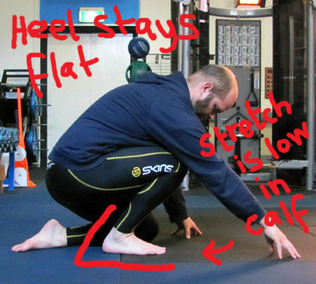

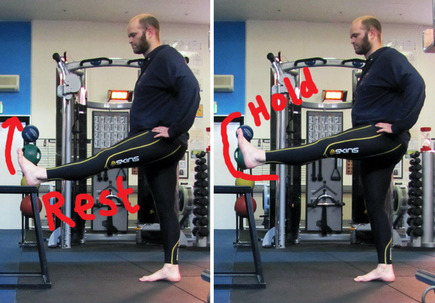

So I wrote about hamstring flexibility in the previous post, and how it relates to squatting deeply. In the pistol squat (pictured), which is essentially a full range of motion squat on one leg, with the other leg held straight out in front – check out how much more of an issue hamstring flexibility becomes. Look at that angle of the back. Even if you were sitting down and totally relaxed, it’s still a pretty significant hamstring stretch. We tend to think of the hamstrings as muscles that primarily work the knee, but they play a massive role in hip extension too, so when you squat down on both legs and the angle between the thigh and belly closes – that position mirrors exactly what you do when you reach forward to touch your toes. Only difference is, the knees are bent when you squat – so you don’t feel the hamstring stretch behind your knee where we are used to – but if you’ve been playing around with the squat and stretch techniques from my previous post, you might be getting familiar with the feeling of a bent-leg load-bearing (weight of your own torso) hamstring stretch. Of course, with the pistol squat – one leg is straight. If you’ve got problems with hamstring flexibility when you’re trying to squat with both legs, this is going to be even harder. If you can’t lift a leg to 90 degrees and keep your back straight, when you attempt a pistol squat, you’ll be pulled backwards. With a pistol squat it’s not so important that you maintain that lower back arch – that’s mostly for when you’ve got both feet on the ground, you’re loading up with weights, and the whole hamstring flexibility pelvic tilt thing is to help you understand why you might be falling backwards, and what to do about it – ie. improve your hamstring flexibility. One of the best and simplest ways of doing this is to relax into a hamstring stretch and hold it for a long time. Up to a few minutes. Every day or so. If it feels tight behind the knee, bend the knee a little – that should move the stretch a little higher into the leg, in the belly of the hamstring, where you want it. You want to feel stretches in the belly of the muscle you’re trying to stretch, not in the tendony insertion areas. It can take a while to develop a good sensitivity for this. If you only work on one thing in preparation for the pistol squat, make it your hamstring flexibility. Leg strength can come later, or from other things you’re doing too. You do, however, need to be confident that your lower back, buttocks and hip flexors are strong. They all work like crazy to complete this technique. In anatomical terms, hip extension is where it’s at. Knee extension only really powers the movement for the relatively easy top half of the movement. It’s powerful hip extension that gets your ass off the ground with one leg.  Something that’s a little controversial, that you absolutely can get away with to a point, is elevating the heel. In the two pictures – one with shoes, one without – you’ll notice that the knee remains in a similar position – not thrusting out too far forwards from the toe, but when you elevate the heel it allows for the body to be in a much more upright position, as long as you still keep your weight on your heels. This means you can keep the hips underneath your shoulders more effectively, rather than swinging the butt way behind you and then levering up through the lower back to stand. Does that make sense? Sometimes when people are weak, and they stand up, it’s not like they’re pressing up from a squat, it’s like they straighten the legs, the chest stays really low, and then they hinge up from the lower back to stand. It’s something you naturally do when your buttocks aren’t very strong, or are too fatigued to help complete the lift. This heels-elevated position still requires a whole bunch of hamstring flexibility, and if you’re too tight you’ll compensate by moving the knee forward. This isn’t necessarily dangerous enough to justify how much people seem to freak out about your knees shooting forwards past the toes, but it does reaveal that the quads are doing all the work, and the hamstrings and buttocks are just coming along for the ride. You’ll never be powerful if you’re only using a third of your possible leg capacity, and over time an imbalance of strong quads relative to weak hamstrings and buttocks can – and frequently does – lead to knee problems. We want to be developing healthy joints over time, not degrading or injuring them with poor movement patterns and the application of inefficient leverage.  The other issue is the heel coming off the ground. If you need to, you can also practice the calf stretch (pictured). See how far you can lean without the heel lifting away from the floor. Don’t lean so far that you feel the stretch low into the heel. It should be in the lower calf/upper achilles area. Unlike most tendons, the achilles is okay to stretch - it’s more elastic than your average tendon. It might or might not be the case that you need to improve your calf flexibility – as much as I’m all about hamstrings in these two posts, it would probably be a good thing for most of us to work on – just try not to mistake hamstring inflexibility for calf inflexibility. When you’re inflexible, or the back of the leg and hips are nonresponsive, your heel will lift up. This makes you super unstable, puts more pressure in the knee, and cripples your ability to drive with the butt muscles. If you’ve got a solid, wooden or hard rubber heel – the kind you find in a dress shoe, that will provide a super strong platform you can stabilise the heel on. So you can actually get away with the knee creeping forward a smidge, you can compensate a little for inflexible hamstrings or calves, and get the back more upright, without sacrificing butt engagement, if you like. Olympic lifters train and compete in fairly high wedges, actually – and if you’re trying to do pistol squats in running shoes, they’re too squishy and very unstable, so it’s going to be harder to balance. Try wearing something more supportive, with a solid sole.  I should talk about what makes for some good prerequisites to practicing pistols. Firstly, you should be able to sit comfortably in either kneeling position, as pictured, for a short period, without your knees aching. If you can’t do this, you aren’t ready for pistols. Of course, you should also be able to do at least fifteen or twenty full range of motion squats with both feet on the ground, also whilst holding a dumbbell or some other kind of moderate weight in your hands. You need to have a conscious awareness of the muscles of your lower back, buttocks and hamstrings. You need to know what it’s like to press through the butt and hamstrings to move some weight. You need to feel confident about your hip, knee and ankle mobility and integrity.  You need to be able to hold one leg straight out in front of you. These really are a few requirements when you add them up. But there are ways to progress that make allowances for relative weaknesses or different stages of progression. You’ll notice in the photo to the left that if you’re practicing on a high step, you don’t need to hold the leg up so high. The benefit of this is that you can reposition the body and work around a degree of hamstring tightness. Notice that when the non-squatting leg extends forwards, the body must lean back further to compensate. This makes it harder to remain balanced on that one small foot. If you can lower the other leg a little, you can move your body’s weight forwards, and this can help with balance and leverage. Of course, you can also practice good old step-ups. You can let your other foot touch down to the ground, transfer your weight on to it, and then step back up from the ground. Try to avoid using the non-squatting leg too much, of course, because if you’re just bounding up from the ground with the calf strength and momentum provided by the other leg, it won’t transfer to the pistol squat so well later on. But it’ll have other benefits for other things, so y’know – do what works for you.  To get better at holding your leg out in front of you, you can practice that movement by itself. Find a bench, step or ledge of some kind that you can rest your heel on, as pictured. Make sure the leg is straight, lift it up and hold for a count of five. Try to keep your supporting leg locked out straight too, and have your supporting foot pointing straight forward, not angled out to the side. If you can’t hold it for five, you’ve chosen a ledge that’s already too high. Find something smaller, and repeat the exercise. Lift for five, rest for five, and repeat up to eight or so times. Then stretch the heck out of your hip flexors and thighs. You’ll probably want to. A good way to do this (under load) is through practicing the Bulgarian split-squat, or rear-foot-elevated-lunge, which is also a good preparatory exercise for pistol squats by itself.  You can also practice a pistol squat as if it were a split-squat. We’re used to doing split-squats on a forwards-backwards alignment, as with the lunge. But you can do it sideways on a low step, as pictured on the far left. It’s kind of same-but-different to using the high step or doing step-ups as described above. Your intention is to be doing a full one leg squat, using the leg that’s on the step, but you allow the other foot also to touch down underneath you and provide you with some assistance. It doesn’t really matter how you apply leverage through the non-squatting foot – you’ll see in the picture I’m resting on the balls of my right foot. Once you’re at the point where you’re confident you can start practicing the full pistol, it might be counterintuitive, but if you hold onto a small weight with your arms out in front of you, it can also help to counterbalance the body (pictured above). It makes some aspects of the lower position much easier, but of course you could be adding several kilograms of weight when you do this, so the actual squat itself gets harder. To assist you in standing up – the leg that you’re holding out straight – keep it straight, but let the heel lower down to touch the ground. That’ll give you a little leverage to stand up with, while still keeping most of your weight over your squatting leg. Then lift the foot back up off the ground and see if you can lower all the way down, with control, before repeating again. And of course, all the same rules apply to this lift as for any other: if your joints feel funky, stop, investigate, and progress in a way that suits you, that’s appropriate to your progression. You should feel the strain in the muscles, not the joints. When you push through muscular pain, you can become stronger, you can become fatigued, you’ll learn something about yourself and intensity either way. However, when you push through joint pain, you become injured. Be attentive to your body and respectful of your limitations, as you seek to exceed them.

7 Comments

Regenia

9/18/2013 06:55:34 am

This is excellent information! I ended up with bursitis in both of my knees shortly after I started running last year. Nearly a year later, I had improved my cardio abilities and rehabbed the knees enough that I wanted to try again. This time I started by getting "real" running shoes to keep my knees from knocking and help with my pronation. They helped and this girl that failed running a mile in high school can run 5k now, ten years later. I noticed some aches in my knees sneaking back though anytime I pushed harder on speed or distance and decided to start lifting free weights to help build up the stabilizing muscles. Since then, I've been learning about how everything connects and feel good about my decision to integrate strength training. When I couldn't get my squats to parallel, I assumed it was my knees and ankles. Then I did some pretty tough reps of Bulgarians and ended up with really sore hams. That lead me to your article on that and then to here. Now I know I need to stretch my hams to keep them from getting so sore next time and to improve my squat depth. Thanks for presenting the info so well- it's stuff I haven't seen anywhere else!

Reply

Chris

9/18/2013 08:13:59 pm

Thanks! I'm very happy to be of help. Many runners struggle with hamstrings, calves and glutes - the whole "posterior chain" thing. Hamstring tightness or inflexibility can relate to glutes and lower back, and pelvic alignment, and a bunch of things, but for simplicity's sake - if you're stretching them, and you feel the tension behind the knee - that's the ligamenty-tendony area. Bend your knee a bit, and you should feel the stretch move up the leg, back of the thigh, to the belly of the muscle. Make sure you're getting the stretch there.

Reply

Brendan

3/6/2014 07:37:29 pm

If I can't do this part, "Firstly, you should be able to sit comfortably in either kneeling position, as pictured, for a short period, without your knees aching. If you can’t do this, you aren’t ready for pistols," What should be my next step?

Reply

Chris

3/7/2014 05:52:41 pm

Thanks Brendan!

Reply

3/15/2018 02:34:58 am

Wonderful article, thanks for putting this together! This is obviously one great post. Thanks for the valuable information and insights you have so provided here.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |