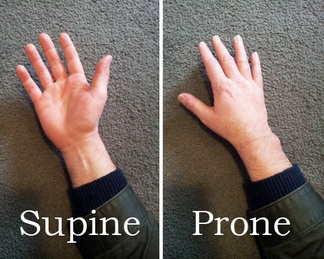

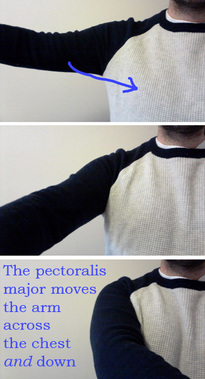

I write sometimes about the importance of feeling the exercise in your muscles rather than your joints. This can be a bit vague. So this will be a (fairly one sided) discussion about the concept of form. I am writing in the context of weightlifting, or in broader terms, resistance training. These concepts might manifest differently in endurance activities like cycling, swimming, walking, aerobics, etc., but the truth remains – when you feel strain, it should feel safe, and it should be in the muscle, rather than in the joint. It’s hard to describe what this is truly like. If you’re training the small stabiliser muscles of the shoulders, the rotator cuff muscles for example, you will feel the strain deep within the shoulder, because that’s where the muscles are, so that’s where they will be working. You shouldn’t feel like the shoulder joint is jamming up, compressing, hyper-extending, or being compromised in any way, though. And that’s the difference I’m talking about. It should still feel muscular, so to speak. People who train for pure strength sometimes deride bodybuilding methods, but I find a lot of old bodybuilding methods work brilliantly for body awareness and sensitivity. Bodybuilders are almost unrivaled in their fine body awareness and muscular control, and their ability to isolate and engage specific body parts. This is a useful skill in certain contexts, including rehab. But when you’re learning to lift weights, to train for strength and some kind of development, it can be both difficult and dangerous to muddle your way through. I don’t know what your body’s like, and your temperament. I have no idea what sort of exercise would be appropriate for you, if any. So the most useful things I can discuss are concepts. Attitudes and approaches. Which brings me to the title of this particular piece. Why do we feel like we need to lift weights in straight lines?  For example – the lateral raise (pictured). I used to buy into the idea that you need to lock your elbows out so your arms are straight, and lift the weights flat out to the side, as if you were standing with your back against a wall and sliding your hands along it. Never mind that this only made my neck and my elbow tight, and I had no sense of the deltoid – the shoulder muscle that this exercise is supposed to work – engaging correctly, it was the way I’d been told, so I did it. Of course, it only gave me grief and never made me strong. Now I find the same exercise useful if I practice one arm at a time (so the neck doesn’t take over and tighten up), with a slight bend in the elbow, while lifting my arm fractionally to the front, instead of dead straight out to the side. On this angle, leading slightly with the index finger or first nuckle, so the palm is angled slightly forwards, rather than completely pronated, I can feel the deltoid muscle working in a very balanced, satisfying way. This seems to be the movement pattern that is useful and good for me. It has helped to develop my strength and body awareness – in my experience the deltoid is a muscle that is very difficult to develop any sensory awareness of, so it’s been a great process of discovery.  The body doesn’t move in straight lines – so why lift in straight lines? Dorian Yates once pointed out that the action of the pectoral muscle (the chest) is to bring the upper arm across the body and slightly down. It’s not flat, so he didn’t like the flat bench press, he preferred the decline bench press, wherein the arm bone – the humerus – moves across and down in relation to the chest/rib cage. Works the chest better – more naturally or more completely. Things often are not flat. Many people avoid the barbell altogether and might practice the dumbbell chest press instead of the bench press, because the longer barbell locks your wrists into a certain position in relation to each other, and stops you from being able to spiral naturally. And strength isn’t about muscles, it’s about how your muscles interact with your bones in the context of gravity. In vague terms, the bones rebound the forces of gravity in spirals. The body makes use of arches and levers and various structures to capitalize on the concept of efficiency. This principle is at the core of tai chi practice, where one of the primary goals is the elimination of tension; take advantage of natural forces. If you are always seeking out hard work, you might find that you are moving with inharmonious patterns, and this won’t help you out in the long term – likely it will only lead to joint fatigue. Ironically, these thoughts came about in relation to an article I read about effective weightlifting exercises where the author described the Zottman Curl as a useless exercise for building the biceps. There are variations, but it essentially involves lifting the dumbbell in a supinated, palm-up position, turning your hand over at the top, and lowering the weight in a pronated position (see the photo at the top of this piece for supination and pronation of the hand/forearm). I understand the critique – the action of pronating and supinating the forearm means you can’t use a super heavy weight, and so the stimulus to the biceps might not be enough to make them grow. But I found it to be a great exercise in pronation and supination of the forearm, which is to say – twisting or spiralling the forearm to rotate the hand from the palm-up to palm-down position. So now I use it as a forearm exercise, and more for mobility than pure strength. If it helps stimulate biceps growth, fine, but if it doesn’t, I don’t care. I’ve also found of late, that I’ve naturally been playing around with a lot of old kung fu styled strength and conditioning exercises. The old masters used push-ups and handstands and squats and chin-ups, and simple good strength training techniques, but also a range of other exercises that might look a bit odd, which exist in the context of martial arts and combat skills, but also worked with the body’s natural movement patterns and in so doing, would strengthen the right muscles naturally. They would include carrying jars using only the fingertips, carrying buckets of water in unusual ways, and many other exercises based around spiralling, twisting, and carrying movements. If you focus on moving naturally and effortlessly, even when (or especially when) you’re carrying something heavy, a lot of questions are answered by themselves. If I had focused more on moving naturally and effortlessly, I would not have wasted so much time on lateral raises that were done inappropriately to my body’s structure. Instead, I would have just moved in ways that were good, and used my own judgment to determine which techniques were appropriate and useful for me, and which were not.

3 Comments

Margo

7/15/2015 09:37:47 pm

Another excellent post, Chris!!!!

Reply

Chris

7/15/2015 10:30:54 pm

Thanks Margo! For your comment and compliment :)

Reply

Leave a Reply. |