|

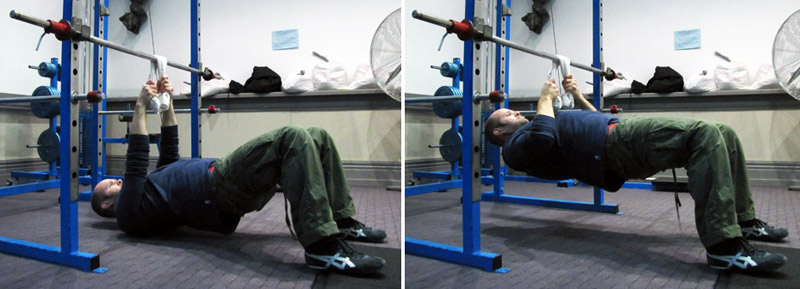

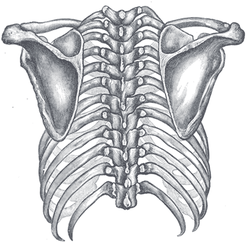

Injuries come in many forms. They may have been recent, or in the distant past, they may be a result of blunt impact trauma – you were hit by a thing – or they may be the result of wrenching or twisting movements, and they might occur as the result of poor movement dynamics over a prolonged period of time – there’s a lot to list, but the last example gets a lot of press these days; the idea that muscle imbalances and tightness results in joint dysfunction, which can manifest in injury and impaired mobility. And then there’s the type of rehabilitation one might require because of all kinds of different illnesses, nervous system dysfunction, or severe trauma which really goes beyond the scope of this post. I would like to be able to write about these more challenging issues one day. But I might still lack the skill. Either way, I like to bring the same attitude to rehab that I try to bring to all my training: make it satisfying and valuable. It doesn’t have to be dull. Sets and reps are of secondary importance when compared to the broader framework of safe and enjoyable movement. Once you’ve got that base covered, then you can look at specifically useful movements, and you can think about appropriate loading parameters. My Osteopath once said he’d rather be a snowboarder than a skier. Yes, snowboarders get more injuries, but their injuries tend to be of the blunt trauma variety which are often easier to rehabilitate. Skiers are more likely to have one ski go one way, the other go another, and therefore – wrenches and tears. These injuries can be more complicated. He also once told me that some injuries heal themselves, but nothing rehabs itself. Fair point. But how do you know when simple rest and time is enough, and how do you know when work is appropriate – and when you’ve made your decision, how do you know how much of what is appropriate? Good questions. I don’t think I can answer them for you. Injuries vary so much from person to person. That’s why we go to see specialists – working out the intricacies of your own particular condition can take time, and if you’re willing to experiment on yourself you might make things worse. But I can explain what simple rehab processes are about. And hopefully, this might give you a sense of what you can start to explore, or it might give you some questions you can take to your specialist, if you have one. So firstly, of course: do nothing that causes you harm. This can be an alarmingly difficult point to stick to. I recently had a problem with my biceps tendon. Everyone says you should rest them, so I rested it, and my shoulder got all jammed up. It only got worse. I started exercising it again, and it’s improved, but I’ve got a long way to go yet. And in this area, I have to be careful to correctly judge between pain and pain. Of all my injuries, this has been remarkable in that it’s the only time where “pushing through pain” has been of benefit. Usually I do not advise that you do that. Pain protects you. It is useful. As far as exercise goes, the main thrust of most rehabilitation programs is to increase joint stability and mobility, which can often be done while working around pain, rather than through it. This approach is largely based on the theory I mentioned above that muscle imbalances and poor movement dynamics have made you vulnerable to injury. But this theory does have holes, and if you’re interested in exploring this further, this article makes for a fascinating read. Really, I am writing about fairly conventional things here. Go read it if you’re curious about pain. In rehabilitation processes, strength usually comes first. Range of motion follows. When you are strong, you can maintain joint stability, and then you learn to open up into a deeper range of motion without sacrificing stability. Learning to move without tension is an incredibly complex and amazing thing. Quite unique. It requires stability and the ability to relax and trust in yourself. A topic for another time, though. Investigate tai chi, if you’re interested.  If you have a shoulder injury, the first item on the agenda is usually to try to improve scapular stability. The muscles that connect the shoulder joint and the shoulder blade must be strengthened. Generally, where shoulders are concerned, people are much stronger at the action of internal rotation than external rotation. This is why you frequently see people being given exercises designed to strengthen external rotation, such as a variety of resistance band pulls. Anything that externally rotates your arm bone in your shoulder socket can be useful to this end. If you stand upright, with your palms facing up as if you’re carrying a bowl of soup in each hand (this position of the palms is known as supination – as in you’re carrying soup – ha ha!), and keep the elbows close to your ribs – from this position start to move your thumbs away from each other, while keeping your elbows fairly close to your torso. The action that your upper arm bone is performing is external rotation. Many of us cannot move very far in this way. The further you go, the harder it gets because your small external rotator muscles are working in opposition to your large internal rotator muscles, which – if tight – will create a lot of resistance. Whether you strengthen your external rotation by practicing little isolated exercises such as these, or by practicing heavier weightlifting exercises like the snatch or the supinated row – this depends on you, what you want to do, and what you can work on without pain. Often, you see people around the place who have hunched shoulders. Either hunched forwards, or internally rotated, or often both. The usual approach to try to resolve this postural condition is both to try to strengthen the muscles that retract the shoulder blades (your scapular retractors, that bring your shoulder blades inwards towards your spine) and strengthen the external rotators.

The theory is this – if you can strengthen the muscles that pull your shoulder blades inwards towards each other, and you can strengthen the muscles that connect the shoulder blades to the shoulder joint – your external rotators, then you can naturally pull the shoulders back, broaden the chest, and promote ‘good posture’. All this happens, theoretically, while you’re not even thinking about it, because your training has successfully, over time, changed your posture. This is more sophisticated than simply telling someone to consciously try to ‘keep their shoulders back’ every minute of every day (which often results in people actually elevating their shoulders which is not what we want). If your solution is to add more tension to a problem that has to do with excessive tension, then it’s a little short-sighted. Just telling people to retract all the damn time only adds tension. It’s also productive to try to resolve the tension that is causing the internal rotation to happen, not to only strengthen the rotators and retractors. Stretches and massage for the front of the shoulders and the chest muscles can be very helpful to this end. When we get massages, we often think of the upper back and shoulders, because this is where the pain and tension is felt. But if the upper back is weak, and the chest is tight, of course the pain will be felt in the weak upper back muscles. They are exposed, elongated, stressed. However, massage for the chest and the front of the shoulders might be more useful, because it can resolve the tension that is pulling the shoulders forwards and creating the tension in the back. When the shoulders are pulled forwards, of course the upper back will experience discomfort – these muscles are constantly working to try to pull the shoulders back, they are in an extended and fatigued state. So the idea that you should walk around all day trying to consciously pull your shoulders back? No. These muscles are already fatigued and traumatised. Allow them to relax. Train them at the gym, properly, and allow them to relax and recover in your day-to-day life away from the gym, and work to resolve the tension in the front of the chest. We can see a similar relationship at work in the hips. The muscles at the front of the hips, the hip flexors, are often tight or short. The action of hip flexion is to bring the knee towards the chest in front of you, as is seen in the angle of the hip when you sit on a chair. As the name implies, the hip flexors, the muscles that flex the hips are in a shortened state when you’re in a seated position, and the extensors – the muscles that extend the hips – the buttocks and hamstrings at the back of the thigh – these muscles are in an extended position when we sit and are weakened or they struggle to ‘fire’ properly. I’m not going to harp on about how people should sit less. I like sitting. I even like a good slouch! You can enjoy these things when you’re fairly pain free. The key is, I think, to train, to work on useful stuff so that your body remains stable, strong and mobile. To resolve what you can, in the time that you can, without it sucking away your life. A sophisticated approach to generalised hip tension and lower back pain – weak/tight hips is often the underlying cause of lower back pain – would have you working to resolve tension and tightness of the hip flexors, while also working to increase the strength of the buttocks and hamstrings. The reason this applies to the lower back is because of pelvic alignment. If your pelvis is out, if muscles are pulling unevenly on it, if there is too much tension or weakness in one area or another, the pelvis pulls on the back. And the lower back pulls on the pelvis – it will try to compensate for weak buttocks by struggling to perform the actions that your butt should be responsible for. And again the same pattern can be seen: strengthen the external rotators of the hips, practice externally rotating your thigh bone, practice extending the hip (moving the thigh away from the torso behind you), and try to resolve the tension in the front of the hip with stretching and massage. Strengthening the buttocks and hamstrings is often the first step in the treatment of knee pain, too. If you are too knee-dominant, or quad (thigh) dominant, it can pull unevenly on the knees. Strengthening the hips can help to even that shit out. It is not true of all injuries and joint problems, but very often if there is a problem with the knees, look to the hips, and if there is a problem with the elbows, look to the shoulders. The vast majority of examples I see of knee pain relate to weakness of the buttocks, relative to the tightness, strength, or muscular mass of the thighs and hip flexors. It’s also good to get familiar with using terms like strength and weakness as relative measuring tools. Nobody and nothing is absolutely strong or weak, and when you identify relative strengths and weaknesses within the body you start to see that these terms exist without judgement, as tools. The body is not weak, nor is it strong, it simply is a body, getting by in a chaotic world. What is strong may be rigid, and what is weak may also be fluid. Pros and cons. What we want from our muscles is a waking state of relaxation, from which we can fully engage when necessary – not constant tension, and therefore constant fatigue. So: the point of most rehabilitation exercises is to increase stability of the joint. To re-balance musculature that might have become imbalanced through the course of life and play. Trying to walk around all day with ‘good posture’ doesn’t work. Training to strengthen your weak muscles, and trying to resolve tension in your tight ones, this is more work, it requires more investigation, but it has a much greater chance for success. And if you’ve decided that you would like to dedicate some time to your physical development, there’s no need to hurry. Self-analysis can give purpose to your training. Simply hopping on a treadmill, or selecting random weightlifting exercises lacks purpose. If you have something to work on, something solid to sink your teeth into, you can come to value a process over time. Training is, in essence, about becoming better at a thing; becoming better at moving in a broad sense. We easily become too obsessed with a static idea of beauty. Training is about motion, not about looking good when you are still. It is not about making you a better person – that’s just status. It’s about making you better at moving, which is a gift, one that we should try to share in as inclusive a way as possible. I’ve never seen an injury that couldn’t be improved upon with work, and I’ve seen many weak muscles and weak areas become strong and pain-free over time. It’s usually a very long process, but it’s worthwhile. It builds your body, it adds to your body in a very positive way, it does not take away, and so it is useful. Bodybuilding as I see it, in a pure sense, is a positive thing. It’s about creating and building and improving, not about stripping away or being ashamed. But I speak in functional terms, rather than aesthetic ones. You may not want big muscles, this is fine. I once heard someone say that weightlifting is a great exercise because it adds to your body, it does not strip away. I loved that. It’s about becoming more, not less, being proud of the space you inhabit, and valuing the body that you have. And it starts from a place of acceptance and non-judgement. One aspect of your body may be weak, another strong, but it’s all yours. It’s nobody else’s. And we don’t need to judge the weak aspects, we don’t need to hold our back or knees in contempt, instead we care for them, we invest in them, we help to bring them up and we repeat this process, strengthening and caring for each weak link in the chain. This is what it means to me, to work from a place of love and value. This is one of many reasons why body-positivity is important to me. So, back to the title of this article: building your body is rehab, diminishing it is not. And one day, we notice that we’ve gotten a bit better in our condition, in our feeling inside, and that the process was worthwhile. These years are going to pass anyway. Might as well be doing something worthwhile. Whatever that is for you. This post has really only touched on some very limited aspects of rehabilitation. There is much to be said, and there are many different conditions one might wish to resolve. Sometimes progress is excruciating. Sometimes it does not come. Sometimes we have to start over again and again. And then we learn something else. Something about the nature of chaos and surrender and patience. But that too, is a topic for another time.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |