There are two primary approaches when it comes to structuring a strength training program: one may choose to prioritize volume or intensity. Usually it’s not possible to do both, although you may work very intensely while training with a great deal of volume. But that assumes you’re kinda advanced already. To clarify: To take a high volume approach, you would focus on getting many, many high quality reps into your session, but you wouldn’t train until failure. If you prefer the high intensity method, you wouldn’t be overly concerned with the number of repetitions, instead you would focus your energies intently on only one work-set, and you’d push as close to muscular failure on that one set as you could. The goal is one intense experience per exercise. There are pros and cons to each approach.

2 Comments

Oftentimes just trying to add more reps doesn’t quite work. It can, in the long term, but day-to-day, it can also feel kindof pointless and frustrating, depending on what you’re working on, and the mentality you bring to the task.

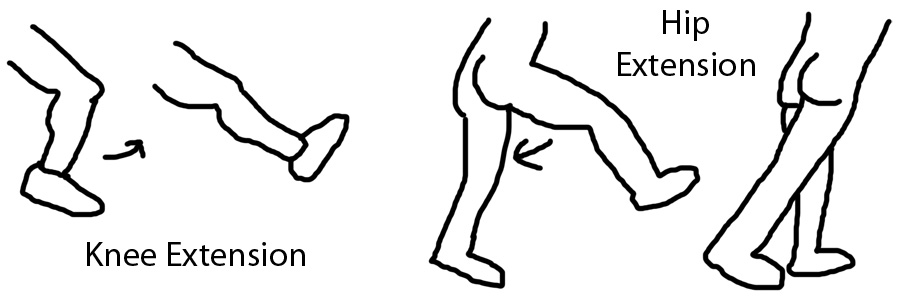

If you want to progress your chin-ups, it’s true that you’ll need to work hard, but it’s better to work at something useful, something that gives you a sense of progress, and to that end, there’s probably something more useful you can do than stubbornly try to muscle through something that isn’t quite working. My usual approach to any technique or exercise is this: identify the weak spot, find exercises that target it specifically, train them, and then in time test your methods by training the original exercise again. See if the weak point has shifted or improved in some way. I think it’s good to remember that what you are testing is the effectiveness of the training methods you have employed, not your worth as a person. If the test fails, then the training methods were ineffective. That’s where the problem lies – there may not be a problem with your work ethic or personality. Instead, it’s just that the training methods did not work for you. Were they poorly prescribed? Did you work too hard or not hard enough? Were the assumptions off? Do you simply need more time or patience before your body can adapt? This will be somewhat technical, so feel free to take your time. If you experience knee or lower back pain when you climb stairs, the following information could be very helpful for you. The purpose of this post is to break down the technique of stair-climbing in order to promote harmonious and efficient movement patterns, built on a foundation of good leverage. In terms of what moves your body from one step to the next, there are two main actions performed in stair climbing: hip extension (where you pull the thigh back and down, away from your torso) and knee extension (where you straighten the leg at the knee joint). Of course, when you move the other leg forwards to the next step, you are flexing at the knee and the hip, but the actions that actually move your body up the staircase are extension and extension. You straighten the knee, and straighten the hip, and this moves your body through space. It is easy not to think in these terms, because as we move forward we think of the leg that is moving forward, but of course it is the leg that remains on the ground that propels our body forwards and in this case upwards, and it is in the action of this leg that we see either efficient or inefficient movement patterns expressed.

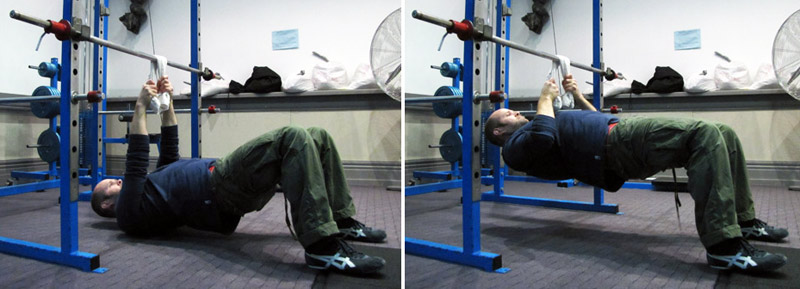

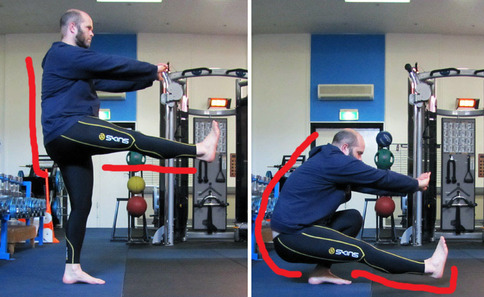

Practicing push-ups is a great way to get strong. As a vague rule of thumb, I like training for either sets of five or sets of ten. I used to be a bit wary of doing heavier work for fewer reps, it’s easy to be unsure if you aren’t confident with your technique, but attempting something that is challenging, which you can complete, is the best way to get strong. It needs to be hard to stimulate development. But you don’t necessarily need to push until failure or train hard all the time – to indulge in the Paleo fantasy for a moment – human evolution – why would high rep training until exhaustion three days a week – why would that be optimal? Is it struggling against exhaustion that stimulates our development? I’m not convinced. Sometimes it’s useful, but sometimes it’s useful to train only a few easy reps, frequently throughout your week. Often that’s not the approach we take – we don’t think it’ll help us get into a smaller pair of jeans or whatever, but if you do start to train like this – easily – it means that training stops being intimidating. It doesn’t have to be an impressive set, you don’t need to worry about whether or not you hit the right numbers, there’s no such thing as failing at a workout. It’s not a test of your character.  Pulling 103 kilograms Pulling 103 kilograms There’s a difference between testing and training. Simply put, training is what you do to develop your strength and athleticism, and testing is what you do if you want to find out where you’re at. In terms of processes, well one is a process and the other isn’t. That’s fairly simple. So training could be thought of as the process of development. If you are fairly strong, you can use chin-ups as a tool, an exercise, for your training. But if you aren’t very strong, chin-ups won’t be a useful tool for training, though they may be a useful tool for testing your strength. It comes down to this: one does not develop by simply attempting a test one cannot do, over and over. Development requires a process. Many coaches and personal trainers – I don’t think it’s a particularly sophisticated approach – treat most or all training sessions as if they’re testing sessions. High intensity, challenging exercises, performed to failure or near-failure, week-in, week-out. I want to grant the benefit of the doubt and say that there is some degree of applicability to this method, but I really don’t know if that’s true. The difficulty is finding the sweet spot, which has led many people to favour training cycles. For a couple of weeks or maybe a month, you’ll perform relatively easy exercises, you’ll get used to the coordination, to moving efficiently and safely. Then for a month you might increase the load, and really start to challenge yourself. And then over the next month or two, you’ll increase the load even more, and shoot for a few one- or three-repetition-maxes. Which is, to say, you’re lifting the most weight you can possibly lift, for the designated number of repetitions. It becomes the test at the end of the training cycle, if you will. Then you take some time off, and rest well. Firstly – to touch on the horizontal pull-up in a little more detail: there are two main ways you can do this, and a bunch of variations. Method one: when you pull your body up to the bar, you aim to bring your nipples or lower ribs towards the bar – your hands are placed around shoulder width or a bit narrower, and this will place most of the emphasis on your lats and mid-back.  So I wrote about hamstring flexibility in the previous post, and how it relates to squatting deeply. In the pistol squat (pictured), which is essentially a full range of motion squat on one leg, with the other leg held straight out in front – check out how much more of an issue hamstring flexibility becomes. Look at that angle of the back. Even if you were sitting down and totally relaxed, it’s still a pretty significant hamstring stretch. We tend to think of the hamstrings as muscles that primarily work the knee, but they play a massive role in hip extension too, so when you squat down on both legs and the angle between the thigh and belly closes – that position mirrors exactly what you do when you reach forward to touch your toes. Only difference is, the knees are bent when you squat – so you don’t feel the hamstring stretch behind your knee where we are used to – but if you’ve been playing around with the squat and stretch techniques from my previous post, you might be getting familiar with the feeling of a bent-leg load-bearing (weight of your own torso) hamstring stretch. People often think the key to squatting deeply is calf and achilles flexibility - especially when they think of the pistol squat - but even though it might feel like that's your limiting factor, it's hamstring flexibility that usually holds you back.

Functional mobility is where strength and range of motion overlap. You’ll commonly see people who are strong, but immobile and who don’t move fluidly or with ease, and at the other end of the spectrum you’ll see people with seemingly great flexibility, but they might just have hyper-mobile or unstable joints. As such, functional mobility is defined not by range of motion or strength, but by both. If you can take your joints through a complete range of motion with stability, you’re mobile. And stability is all about strength and awareness. When I started squatting heavy and really building up my hamstrings, I found I could sink into the front splits much further. They say that weightlifting makes you tight, but because I increased my strength, I could stretch further without feeling vulnerable. Everything felt safer. It’s not about just stretching and increasing your flexibility in a passive sense – it’s about increasing your range of motion with strength and stability. If you’re very tight, you could develop a lot by learning to relax into a stretch, but probably what you want to focus on is being strong and stable in an extended, elongated or stretched-out position, rather than just trying to stretch further. It may be a little premature, but if you’ve been following my various posts on chin-ups – maybe you are at the point where you can do two or three chin-ups (full range of motion or not), and you might be noticing that it doesn’t suddenly get any easier to progress.

When people get to the point where they can do a few reps of an exercise with okay form, there’s a tendency to abandon the less advanced training techniques. Once you can do push-ups from the feet, even if you can’t go all the way down, or the form’s a bit shaky – people give up on doing push-ups from the knees, thinking of them as cheating. But there’s no such thing as cheating, really – you’re either doing the technique or you’re not, and there are various techniques at a range of difficulty levels, and if you need to be training anything, practicing techniques that help you to progress is always going to be best. |